1. Introduction

Intractable epilepsies, also known as refractory or drug-resistant epilepsies, are a group of epileptic disorders that are difficult to control with medication. These epilepsies are particularly challenging to manage in the pediatric population, as they often have a significant impact on the child’s quality of life, including their cognitive, social, and emotional development. This writeup aims to provide an overview of intractable epilepsies in children, their causes, diagnosis, treatment, and long-term outcomes.

2. Causes

Causes of intractable epilepsies in the pediatric age group can be broadly classified into the following categories:

A. Genetic causes:

Certain genetic mutations or syndromes are associated with an increased risk of developing intractable epilepsy. Examples of these include:

- Dravet syndrome: A severe form of epilepsy caused by mutations in the SCN1A gene, which encodes a voltage-gated sodium channel. Children with Dravet syndrome often experience prolonged seizures and developmental delays.

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: A rare and severe form of epilepsy characterized by multiple seizure types, cognitive impairment, and a specific EEG pattern. The genetic basis for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is not fully understood, but several genetic mutations have been associated with the condition.

- Tuberous sclerosis complex: A genetic disorder caused by mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 genes, leading to the growth of benign tumors in various organs, including the brain. Epilepsy is a common feature in children with tuberous sclerosis complex, and seizures are often difficult to control.

B. Structural brain abnormalities:

In some cases, intractable epilepsy in children may result from structural abnormalities in the brain. These can include:

- Malformations of cortical development: Abnormalities in the structure of the cerebral cortex, which can lead to focal epilepsies that are often drug-resistant.

- Brain tumors: Seizures may arise from the presence of a brain tumor, and in some cases, these seizures can be difficult to control with medications.

- Post-traumatic epilepsy: Brain injury resulting from trauma can cause seizures, which may become intractable in some cases.

- Perinatal insults: Severe brain injury or lack of oxygen during birth can lead to epilepsy, which may be difficult to control with medications.

C. Metabolic disorders:

Some metabolic disorders can lead to the development of intractable epilepsy in children. Examples include:

- Mitochondrial disorders: These are a group of genetic disorders that affect energy production in cells, and they can cause a variety of neurological symptoms, including seizures that are difficult to control.

- Glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) deficiency: A genetic disorder that impairs glucose transport into the brain, causing seizures, developmental delays, and movement disorders.

D. Immune-mediated causes:

In some cases, intractable epilepsy in children may result from an immune-mediated process, such as Autoimmune encephalitis in which there isinflammation of the brain caused by an abnormal immune response. This can lead to seizures that are difficult to control with medications.

E. Unknown etiology:

Despite extensive investigation, the cause of intractable epilepsy remains unknown in some children. These cases are often referred to as “cryptogenic” or “idiopathic” intractable epilepsies.

3. Epidemiology

Understanding the epidemiology of intractable epilepsies in children is crucial for healthcare planning, resource allocation, and guiding research efforts. The prevalence and incidence of intractable epilepsies in the pediatric population can vary depending on the specific syndrome or etiology, as well as the geographical region and population studied.

A. Prevalence and incidence:Intractable epilepsies account for approximately 20-30% of all pediatric epilepsy cases. The overall prevalence of epilepsy in children is estimated to be around 3.2 to 5.5 per 1,000, and considering the proportion of intractable cases, the prevalence of intractable epilepsies in children ranges from 0.64 to 1.65 per 1,000.

B.Age of onset:The age of onset for intractable epilepsies in children varies depending on the specific etiology. Some genetic syndromes, such as Dravet syndrome, typically present within the first year of life, while other causes like Lennox-Gastaut syndrome may have a later onset, usually between 2 to 8 years of age. In general, early-onset epilepsies tend to have a higher likelihood of becoming intractable.

C. Gender differences:Intractable epilepsies affect both male and female children, but some studies suggest a slightly higher prevalence in males. The gender differences in the prevalence of intractable epilepsy may be attributed to the specific etiology or genetic factors.

D. Geographical and population variations:The prevalence and incidence of intractable epilepsies in children may vary across different geographical regions and populations due to factors such as genetic diversity, access to healthcare, and diagnostic capabilities. For example, the prevalence of intractable epilepsy in resource-limited settings may be underestimated due to inadequate diagnostic and treatment facilities.

E. Risk factors:Several risk factors may increase the likelihood of developing intractable epilepsy in children. These include a family history of epilepsy, early age of seizure onset, a high initial seizure frequency, and the presence of specific genetic mutations or structural brain abnormalities.

4. Symptoms

Symptoms of intractable epilepsies in the pediatric age group can vary widely, depending on the underlying cause, specific syndrome, and the age of the child. The primary symptom of these epilepsies is recurrent, drug-resistant seizures. However, the seizure types, associated symptoms, and comorbidities can differ across individuals.

A. Seizure types:

Intractable epilepsies can present with various seizure types, including focal (originating from a specific area of the brain) or generalized (involving the entire brain) seizures. Some children may experience multiple seizure types, such as in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Common seizure types observed in intractable epilepsies include:

- Tonic-clonic seizures: Characterized by stiffening of the body (tonic phase) followed by rhythmic jerking (clonic phase).

- Absence seizures: Brief lapses in awareness or unresponsiveness, often with staring spells.

- Myoclonic seizures: Sudden, brief muscle jerks that can affect a single limb or the entire body.

- Atonic seizures: Sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to falls or head drops.

- Focal seizures: Manifesting with a variety of symptoms, depending on the brain region involved, such as abnormal sensations, involuntary movements, or altered consciousness.

B. Frequency and severity:Children with intractable epilepsy often experience frequent and severe seizures, which can significantly impact their daily functioning and quality of life. The frequency of seizures can range from daily to monthly, and the severity can vary from mild to life-threatening.

C. Developmental and cognitive impairments:Many children with intractable epilepsies experience developmental delays and cognitive impairments. These may include difficulties with learning, memory, attention, and problem-solving. The degree of impairment can range from mild to severe and may worsen over time, particularly if seizure control remains poor.

D. Behavioral and emotional issues:Children with intractable epilepsies are at an increased risk of developing behavioral and emotional problems. These can include hyperactivity, aggression, anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal. The presence of these issues can further impact the child’s overall functioning and quality of life.

E. Sleep disturbances:Sleep disturbances are common in children with intractable epilepsy, including difficulty falling asleep, frequent night awakenings, and daytime sleepiness. Sleep problems can exacerbate seizure frequency and severity, as well as negatively impact cognitive and emotional functioning.

F. Motor and coordination problems:Some children with intractable epilepsies may experience motor and coordination problems, such as poor balance, muscle weakness, and difficulty with fine motor skills. These issues can affect the child’s ability to perform daily tasks and participate in age-appropriate activities.

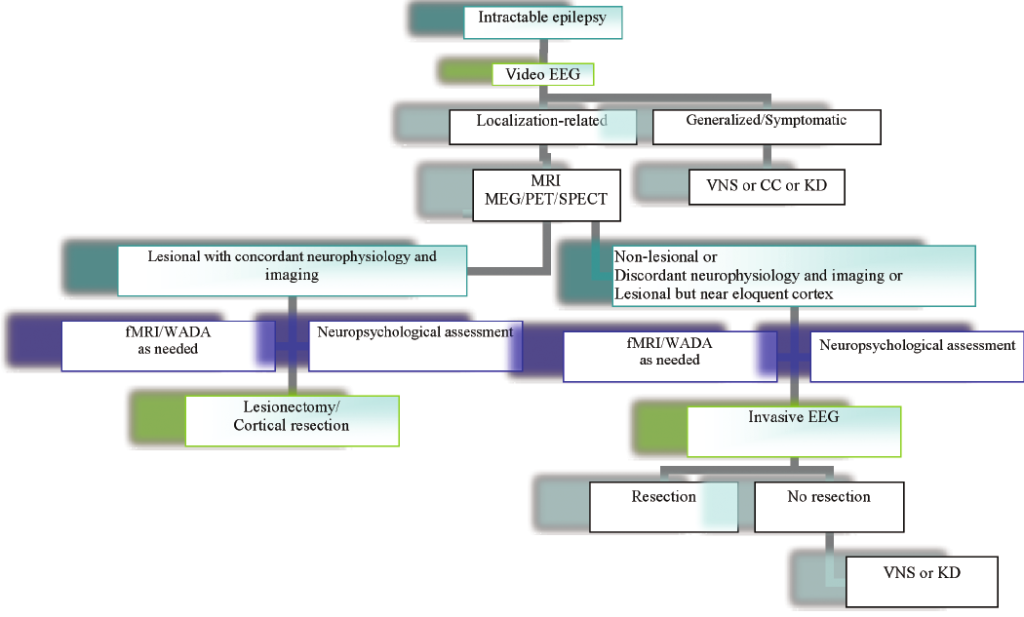

5. Pointers to Diagnosis

Diagnosis of intractable epilepsy in children relies on a combination of clinical history, electroencephalogram (EEG) findings, neuroimaging, and genetic testing. Early recognition of refractory seizures and accurate identification of the underlying etiology are crucial for guiding appropriate treatment strategies.

6. Natural History

The natural history of intractable epilepsies in children is variable, depending on the specific syndrome or cause. Some children may experience a reduction in seizure frequency over time, while others continue to have uncontrolled seizures despite multiple treatment trials. The long-term prognosis is generally poorer than that of children with more easily controlled epilepsy.

7. Treatment Options

Treatment options for intractable epilepsies in the pediatric age group aim to achieve optimal seizure control, minimize adverse effects, and improve the child’s quality of life. Given the drug-resistant nature of these epilepsies, a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions is often required. Here, we elaborate on various treatment options for intractable epilepsies in children:

A. Pharmacological treatment:Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the first-line treatment for children with intractable epilepsy. Several AEDs are available, and the choice of drug depends on factors such as the specific seizure type, age, and potential side effects. In cases of intractable epilepsy, multiple AEDs may be tried, often in combination, to achieve the best possible seizure control.

B. Dietary therapies:

Dietary therapies, such as the ketogenic diet, modified Atkins diet, and low glycemic index treatment, can be beneficial for some children with intractable epilepsy. These diets are typically high in fat and low in carbohydrates, which may help to reduce seizure frequency by altering the brain’s energy metabolism. Dietary therapies should be carefully monitored by a nutritionist or dietitian experienced in managing epilepsy.

C. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS):VNS is a non-pharmacological treatment option for children with intractable epilepsy who have not responded to AEDs or are not suitable candidates for epilepsy surgery. The VNS device is implanted under the skin of the chest and delivers electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve in the neck. This stimulation can help reduce seizure frequency and severity, although it is not a cure for epilepsy.

D. Responsive neurostimulation (RNS):RNS is another neuromodulation therapy, similar to VNS, but it involves the implantation of a device within the skull that directly stimulates the brain. The RNS system detects abnormal electrical activity and delivers targeted electrical stimulation to interrupt seizures. This treatment option is reserved for children who have not responded to other therapies and are not candidates for epilepsy surgery.

E. Epilepsy surgery:Epilepsy surgery can be an effective treatment option for children with intractable epilepsy when AEDs and other non-surgical treatments have failed. The goal of epilepsy surgery is to remove or disconnect the seizure focus in the brain. Various surgical procedures can be performed, including:

- Focal resection: Removal of the seizure focus, such as in cases of cortical dysplasia or brain tumors.

- Hemispherectomy: Removal or disconnection of one cerebral hemisphere, usually reserved for cases with extensive brain damage or severe epilepsy affecting one side of the brain.

- Corpus callosotomy: Severing the corpus callosum, the structure that connects the two brain hemispheres, to prevent the spread of seizures between hemispheres.

- Multiple subpial transection: Making small cuts in the brain to interrupt the pathways of seizure spread without removing brain tissue.

F. Cannabidiol (CBD) and other alternative therapies:CBD, a non-psychoactive compound derived from cannabis, has shown promise as an adjunctive treatment for some children with intractable epilepsy, particularly Dravet and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes. Other alternative therapies, such as acupuncture, biofeedback, and herbal remedies, have been explored but lack robust evidence to support their use in treating intractable epilepsy.

It is crucial to individualize the treatment approach for each child, taking into consideration the specific etiology, seizure types, and the child’s overall health and developmental needs. A multidisciplinary team, including pediatric neurologists, epileptologists, neurosurgeons, dietitians, therapists, and other healthcare professionals, should be involved in the comprehensive care and managementof children with intractable epilepsy.

A multidisciplinary team, including pediatric neurologists, epileptologists, neurosurgeons, dietitians, therapists, and other healthcare professionals, should be involved in the comprehensive care and management of children with intractable epilepsy. This approach ensures that all aspects of the child’s health and well-being are addressed, and the most appropriate treatment plan is implemented.

8. Timing of Surgery

The timing of surgery for children with intractable epilepsy is an important consideration, as it can significantly impact the outcome and overall quality of life for the child. Several factors need to be considered when determining the appropriate timing for epilepsy surgery:

A. Failure of medical management: Surgery is usually considered when a child has failed to achieve adequate seizure control with two or more appropriately chosen and dosed antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). This indicates that the epilepsy is drug-resistant and may be more amenable to surgical intervention.

B. Identification of a surgically amenable lesion: The presence of a well-defined, surgically accessible lesion or seizure focus is crucial for successful epilepsy surgery. This may include lesions such as cortical dysplasias, brain tumors, or hippocampal sclerosis. Advanced neuroimaging techniques and video-EEG monitoring are typically used to localize the seizure focus and determine its suitability for surgery.

C. Age of the child: Although there is no strict age limit for epilepsy surgery, the timing of surgery should be carefully considered in relation to the child’s developmental needs. Early surgical intervention may be beneficial in certain cases, as it can prevent ongoing damage to the developing brain and reduce the risk of long-term cognitive, behavioral, and motor impairments.

D. Impact on quality of life: The decision to proceed with surgery should take into account the impact of ongoing seizures on the child’s quality of life. Factors such as the severity and frequency of seizures, associated cognitive and developmental impairments, and the child’s ability to participate in age-appropriate activities should be considered.

E. Risks and benefits of surgery: The potential risks and benefits of epilepsy surgery should be weighed carefully for each individual child. The surgical team, along with the child’s family, must consider factors such as the likelihood of seizure freedom, potential postoperative complications, and the impact on the child’s overall health and well-being.

F. Multidisciplinary evaluation: A comprehensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, including pediatric neurologists, epileptologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and other healthcare professionals, is essential for determining the most appropriate timing for surgery. This evaluation ensures that all aspects of the child’s health, seizure history, and developmental needs are taken into account when making the decision to proceed with surgery.

9. Recovery and Rehabilitation

Recovery and rehabilitation following epilepsy surgery depend on the specific surgical procedure and the child’s individual needs. Postoperative care may include physical, occupational, and speech therapy to address any functional deficits, as well as ongoing management of seizures and other medical issues.

10. Outcome

The outcome of children with intractable epilepsy is highly variable and depends on factors such as the underlying cause, seizure severity, and treatment response. While some children may experience significant improvements in seizure control and quality of life following treatment, others may continue to struggle with uncontrolled seizures and associated comorbidities.

11. Follow-up

Long-term follow-up is essential for children with intractable epilepsy, as ongoing management and monitoring of seizure control, medication side effects, and developmental progress are crucial. Regular follow-up appointments with a pediatric neurologist or an epilepsy specialist are recommended, along with routine EEGs and neuroimaging as needed. Additionally, a multidisciplinary approach involving other healthcare professionals such as therapists, nutritionists, and social workers can provide comprehensive support for the child and their family.

12. Summary

Intractable epilepsies in children are a complex and challenging group of disorders that require a multidisciplinary approach to management. Early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment are vital in optimizing outcomes for affected children. Although the prognosis varies depending on the underlying cause and treatment response, ongoing support and follow-up care can help improve the overall quality of life for children with intractable epilepsy and their families.

13. Disclaimer

This website provides general information about healthcare topics to help individuals make informed decisions and connect with medical professionals for support. However, it is important to note that the information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. It is recommended to always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare provider for any medical questions or concerns. Reliance on any information provided on this website is solely at your own risk. If you are interested in scheduling an appointment with a qualified specialist in Pediatric neurosurgery, you can contact us via phone or message on Telegram / WhatsApp at +91 8109 24 7 365.